| Movable

Bridge Needs

According to information from the Federal

Highway Administration‘s data, there

are approximately 892 movable bridges in the

United States National Bridge Inventory (NBI)

on the public roads in the United States.

According to FHWA’s National Bridge

Inspection Standards approximately 589 (66%)

of these of these movable bridges are structurally

or functionally obsolete. This data does not

consider the need for movable bridges in new

locations.

Economic Issues

The cost to construct or reconstruct a movable

bridge can easily exceed the cost of a comparable

fixed bridge meeting similar design parameters

by 3 to 6 times. For example, a bascule drawbridge

recently constructed in Miami, Florida —

the Second Avenue drawbridge — costs

approximately $44 million while a comparable

fixed bridge without the vertical navigation

clearance requirements would have cost approximately

$10 million. Another example is the vertical

lift drawbridge under construction in Houma,

Louisiana — the Daigleville Bridge.

It costs approximately $6 million dollars

while a comparable fixed bridge without the

vertical navigation clearance requirements

costs approximately $1.5 million. Because

of the high costs of movable bridges, many

communities cannot afford to replace their

existing, deficient movable bridges or to

construct new movable bridges on navigable

stream crossings where needed.

The low-level movable bridge crossing is

the most common application for movable bridges

and the substantial part of the discussion

herein. A low-level movable bridge alternative

will typically have the lowest construction

cost and the highest daily operating costs

in terms of power consumption and manpower

required. Low-level movable bridge crossings

necessarily expose the movable span to collision

damage by the most massive components of marine

vessels that are nearest to the water surface.

This results in high economic losses due to

severity of the damage and loss of service

for the months that are necessary to effect

emergency repairs.

The high-level fixed bridge crossing is

an alternative to the low-level movable bridge

crossing. Due to its height above the water

— the vertical clearance required over

the navigation channel — the high-level

fixed bridge requires the construction of

substantial substructures and costly approach

structures making this alternative typically

a more expensive alternative to construct

than a low-level movable bridge. A high-level

fixed bridge normally takes substantially

longer to construct than a low-level movable

bridge and it can permanently disrupt a community

separated by a navigable waterway.

The semi-high-level movable bridge crossing

combines a movable bridge with longer approaches

to the semi-high-level crossing. It combines

some of the higher construction costs of the

high-level fixed bridge with the ongoing operating

costs of a low-level movable bridge making

this alternative usually the most expensive.

An intersecting high volume marine channel

and high traffic volume highway facility in

an urban environment, where limiting the frequency

of bridge openings to accommodate only the

larger vessels and a limited length of approach

structures is acceptable, this configuration

becomes feasible by the unique conditions

if not economically the best alternative considering

user costs.

Construction Issues

With the prevailing traffic conditions in

most communities, shutting down an existing

route segment on the public street system

for 2 to 4 years to reconstruct a movable

bridge is generally unacceptable. The aforementioned

Second Avenue drawbridge in Miami, Florida,

took over 2 years to construct. Similarly,

the Daigleville drawbridge in Houma —

expected to be completed by January 2004 —

will have taken nearly 3 years to construct.

For the Daigleville drawbridge, there has

been at least one petition filed by frustrated

businesses and property owners concerned about

its lengthy construction time. While construction

time for movable bridges may be expedited

as much as it is possible, it is not uncommon

that unanticipated, additional construction

time is required to deal with unexpected problems

associated with the complex nature of the

design and construction of the conventional

movable bridges.

History

Conventional Movable

Bridge Types

In his history of movable bridges, titled

Remember the Past to Inspire the Future

– Historic Development of Movable Bridges,

John A. Schultz, Jr., SE, reveals that the

modern versions of the three conventional

movable bridge types — namely the vertical

lift, bascule and swing drawbridges —

are 19th century developments. Each of the

conventional movable bridge types features

a unique movement including vertical translation,

vertical rotation and horizontal rotation

respectively.

One may ask, why did these bridge movements

become standards? From a review of bridge

history and given 19th century technology,

bridges with these three movements were the

easiest to construct, the most cost effective

and the most reliable to operate. It appears

that once these three standards were available,

the 19th century spirit of movable bridge

innovation may have faded into simply updating

and improving on the three standards.

Retractable Drawbridge

The retractable drawbridges — also referred

to as the traversing or sliding drawbridge

— has been designed and constructed

in the past. However, it never gained the

broad acceptance of the conventional moveable

bridge types — vertical lift, bascule

and swing drawbridges. A reason the retractable

drawbridge did not come into common use is

explained by F. C. Kunz, CE in his book, Design

of Steel Bridges — Theory and Practice

for the use of Civil Engineers and Students,

1915, in Chapter XIV on Movable Bridges and

Turntables page 275. He writes,

A traversing bridge is not desirable as it

requires more power than any other kind and

is slow of motion. It has been used in only

a few cases for railroad bridges, but has

proved satisfactory for small highway bridges.

Given the technology of 90 years ago, the

retractable drawbridge was apparently not

a technically or economically a competitive

choice. However, it is believed that the two

disadvantages expressed by Kunz — excessive

power consumption and a slow operation —

can be effectively overcome through invention

and using current technology. This will be

discussed later in more detail.

Existing Limitations

There are design requirements that tend

to make the conventional movable bridge types

— vertical lift, bascule and swing drawbridges

— expensive to build. To operate and

move the movable spans to a position that

provides the required unobstructed navigation

clearances, the conventional movable bridge

types typically require components of their

structures to be larger and/or more complex

than would otherwise be required of the comparable

fixed bridge necessary to span the navigation

channel and accomplish the intended traffic

carrying purpose.

The vertical lift drawbridge requires

the movable span to be translated vertically

enough to provide for the maximum vertical

navigation clearance required above the water.

To do this, it requires an expansive and massive

superstructure to support the span, counterweights,

sheaves, cables, and power and control equipment

to lift the movable span typically 50' to

a 100' or more vertically. This superstructure

is very expensive to build.

The bascule drawbridge requires

the movable span — a bascule leaf —

to be rotated vertically up and away from

the navigation channel to provide the maximum

horizontal navigation clearance and unlimited

vertical navigation clearance. Depending on

the depth of a bascule girder, the distance

between piers supporting the bascule girder

is typically greater than what is necessary

to meet the maximum horizontal navigation

clearance. Live load resistance provisions

— particularly for a double leaf bascule

drawbridge — and the counterweight configuration

typically result in a massive pier required

to support a bascule span.

The swing drawbridge requires the

movable span to be rotated horizontally parallel

to — and out of — the navigation

channel to provide the maximum horizontal

navigation clearance and unlimited vertical

navigation clearance. The swing span rests

on a turntable or pivot pier for which its

center and the center of rotation of the span

typically coincide and it must be horizontally

offset from the edge of the navigation channel

by more than half the width of the movable

span. This is necessary to locate the movable

span outside of the navigation channel when

in the opened position. As a result, a swing

drawbridge superstructure and substructure

are oversized to meet the offset and operation

requirements. Wider roadways require greater

offsets and therefore greater size for the

turntable pier and length of movable span

for the swing drawbridge. Because of the required

offset, swing drawbridges are normally best

suited for relatively narrow spans of those

providing for fewer traffic lanes. Of the

conventional movable bridge types, the swing

span drawbridge requires the most right of

way in which to operate the movable span.

Innovation

Considering the opportunities that may be

available in the use of 21st century technology,

and the specific needs of highway transportation

and the nature of highway transportation facilities

today; it is suggested that it may be the

right time to — as Shultz’s title

suggests — Remember the Past to

Inspire the Future. It may be time to

rekindle the 19th century spirit of movable

bridge innovation by leveraging 21st century

technology to address the functional and economic

needs of the 21st century.

Goals

Every movable bridge location has its own

unique site parameters that require consideration

in the design. When reviewing initial design

and construction costs, construction time,

maintenance and operations costs, and safety

issues both during and after construction,

it appears that the costs for every movable

bridge project has the potential to be reduced

substantially through innovation in movable

bridge design. For this reason, it is reasonable

that an innovation in movable bridge technology

should be sought outside of the three conventional

movable bridge types. Such an innovation should

provide a high quality facility that can be

constructed, operated and maintained easily;

provided at a significant cost savings; and

constructed in a minimum time.

Could there possibly be an innovative movable

bridge design that may be equal to or more

effective than the time-tested conventional

movable bridge types and yet draws on the

knowledge base developed for them? If there

is such a type of movable bridge, it most

likely would be discovered through the aforementioned

tenet, Remember the Past to Inspire the Future,

and in doing so, the best conventional features

would be extracted. The effectiveness of any

type of movable bridge measured against the

conventional movable bridge types is in the

context of true practical worth relative to

• cost to design and construct

• time to construct

• cost and speed of operation

• cost and frequency of maintenance

and

• general safety concerns.

In his book titled, Design of Steel Bridges

— Theory and Practice for the use of

Civil Engineers and Students, 1915 in

Chapter XIV on Movable Bridges and Turntables

page 273 F.C. Kunz, CE, writes

It is impossible to give any general rule

as to which kind of bridge is best adapted

in a certain case, as there are many factors

to be considered. The following general principles

should be observed:

(1) When the bridge is closed it should be

as nearly as possible a fixed span.

(2) The machinery should be designed so that

the bridge can be easily operated while moving.

The most simple design which gives the least

first cost and cost of operation is the best.

(3) The structural and machinery parts of

the bridge should be separate; that is, when

the bridge is closed, acting as a fixed span,

the machinery parts should not receive any

stress.

Lift-Slide Drawbridge

The economic and construction issues experienced

with the conventional movable bridge types

suggest that there may be a niche for a lower

cost movable bridge type. It is proposed that

a retractable drawbridge innovation, the lift-slide

drawbridge - patent pending, may offer a lower

cost alternative to the conventional movable

bridge types. Its principal benefit appears

to be reducing the construction costs by an

estimated 30 to 50 percent making movable

bridge projects more affordable. Some broad

goals achievable with this simple, innovative

drawbridge design are

• free up millions of transportation

dollars to fund additional, badly-needed highway

transportation projects

• accelerate the construction process

reducing construction time to a year or less

and

• allow opportunity for improvement

in movable bridge operation, maintenance and

safety.

The lift-slide drawbridge with a unique variable

load counterweight system — patent pending

— was conceived to meet the above goals

in addition to incorporating the best features

and avoiding the disadvantages of the conventional

movable bridge types. The anticipated features

of the lift-slide drawbridge are

• a high quality, safe highway bridge

• rapid and simple operation

• accessible components for safe and

easy maintenance

• low maintenance requirements —

as a fixed span, machinery parts do not support

loads

• can be maintained while in service

• can be constructed without disrupting

marine traffic

• can be constructed safely and quickly

• unlimited vertical clearance for marine

traffic

• structure is well protected from damage

by marine traffic

• is scalable in width so that it can

be designed to accommodate one to six lanes

of traffic

• is scalable in length so that it can

accommodate a horizontal navigation clearance

up to 150' and perhaps more

• is scalable in duty so that it can

be designed to accommodate light or heavy-duty

traffic

• can be built inexpensively (scalability

in width, length and duty makes it possible

for a drawbridge to be sized to meet the needs

of a location with a resultant substantial

cost savings)

• can be built within existing or minimal

right-of-way, and

• the structure is attractive, low profile

and would be welcome in any neighborhood.

Invention

The main components of the lift-slide drawbridge

invention include

• the movable or retractable span

• the lifting apparatus in the lift-slide

mechanism,

• the variable load counterweight system

in the lift-slide mechanism and

• the sliding apparatus in the lift-slide

mechanism.

The anticipated advantages of the retractable

drawbridge previously discussed can be realized

with the development and deployment of the

lift-slide drawbridge described. The lift-slide

drawbridge design will be a simple, yet rapid

operating, retractable drawbridge. By providing

a short initial vertical lift of the retractable

span to clear the adjacent bridge approaches,

the conflict between them is avoided. The

lifting of the heavy retractable span led

conceptually to an energy efficient and cost

effective scissors lift apparatus assisted

by a variable load counterweight system. The

resulting reduced power consumption expected

allows the use of smaller motors for the system

with overall cost savings. The power consumption

for operating the lift-slide drawbridge is

expected to be similar to — or possibly

less than — that for the conventional

movable bridge types.

Unlike the conventional movable bridge types,

the lift-slide drawbridge operation will not

generally require components of their structures

to be larger and/or more complex than would

otherwise be required of the comparable fixed

bridge necessary to span the navigation channel

and accomplish the intended traffic carrying

purpose. This is because

• the operation of its movable span

is within its plan limits

• the open position for the movable

span that provides unobstructed navigation

clearances coincides with the approach spans

• the substructure components will be

approximately the same size as that required

for a fixed bridge and

• the movable span (deck) components

will be approximately the size of those for

a fixed bridge.

|

| |

Movement

The lift-slide drawbridge is a movable bridge

invention that when it is supporting roadway

traffic it is a two-span continuous structure.

When roadway traffic is not present and it

is being operated (retracted), it is an equal-arm,

cantilever beam structure. Operationally,

it is initially lifted (translated) vertically

to an elevation that will clear it over the

adjacent approach spans, then it is retracted

from the navigation channel by sliding (translating)

it horizontally back over the adjacent approach

span.

The three operating positions of the bridge

follow in more detail:

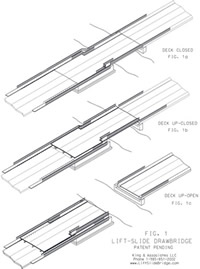

• In the down-closed position as shown

in Figure 1a with roadway traffic present,

the bridge is a two-span continuous beam structure

supported directly on its by piers with one

span over the navigation channel.

• In the up-closed position as shown

in Figure 1b with roadway traffic not present,

the bridge is an equal-arm cantilever beam

structure supported on the lift-slide mechanism

with one cantilever span over the navigation

channel and lifted vertically by the lift-slide

mechanism high enough to clear the adjacent

spans on the bridge approach and any other

obstacles when the span is retracted horizontally

from the navigation channel.

• In the up-open position as shown in

Figure 1c with roadway traffic not present,

the bridge is an equal-arm cantilever beam

structure supported on the lift-slide mechanism

and retracted horizontally from the navigation

channel with one cantilever span over the

adjacent spans on the bridge approach. As

a design alternate, in up-open position the

adjacent approach spans may be used to support

the bridge deck by means of rollers attached

to the underside of the retractable span.

|

| |

Operation

When in the down-closed position, the retractable

span is supported directly by the piers and

functions as a two-span continuous beam fixed span for live loads.

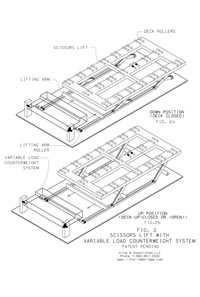

To operate the span, roadway traffic service

is ceased and the vertical lift apparatus

the lift-slide mechanism is activated. It

is a hydraulically driven scissors lift apparatus

used in conjunction with the variable load

counterweight system to provide an effective

means to lift the retractable span typically

2.5' to 5.0' to clear adjacent approach spans

as shown in Figures 2a and 2b.

Once in the up-closed position, the equal-arm

cantilever beam structure is supported by

the slide-lift mechanism the sliding apparatus

driver is activated to retract the cantilevered

span translating it horizontally to the up-open

position thus opening the navigation channel

to marine traffic. The sliding apparatus is

secured atop the lift-slide mechanism and

coupled to the bottom of the retractable span.

It allows the retractable span to slide or

translate horizontally over the adjacent approach

spans and the navigation channel while in

the up position as shown in Figures 3 and

4.

|

| |

| |

|

| |

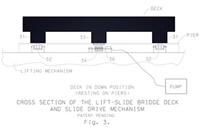

Following the item numbers shown in Figures

3 and 4 and in braces in this text, the sliding

apparatus driver consists of a span rack [33]

attached to the underside of the retractable

span. It is engaged by a span pinion [34]

coupled to a span drive motor [36] that are

both attached to the lift-slide mechanism.

The retractable span is guided by span guides

[31] that are attached to the underside of

the retractable span seated in flanged wheel

trucks [32] that are attached to the lift-slide

mechanism.

Variable Load Counterweight

Movable bridges having a vertical lift motion

require a counterbalance to effectively and

safely handle the heavy load of the movable

span. The only practical counterbalance design

for the large vertical movements of a vertical

lift drawbridge is counterweights suspended

by cables passing over sheaves supported at

the top of lift towers. Since the lift-slide

drawbridge only requires the lifting of its

retractable span a few feet, the traditional

counterweight design if feasible would appear

to be a prohibitively expensive and complex,

so a simple innovative counterweight system

was invented.

|

| |

| |

|

| |

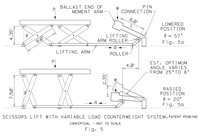

The variable load counterweight system shown

in Figures 5 and 6 is a counterweight designed

to counter the characteristic forces inherent

in operating the scissors lift apparatus proposed

to lift the span. This is done by providing

a counterweight coupled to the scissors lift

apparatus via its lifting arm. The counterweight

is mounted on — and cantilevered from

— a hinged support and supported by

a lifting arm attachment roller.

Raising or lowering of the scissors lift

apparatus moves the lifting arm attachment

roller support point on the counterweight

and thereby varies the length of the moment

arm to the ballast end of the counterweight.

The change in length of the moment arm between

the lifting arm attachment support point roller

and the ballast end of the counterweight is

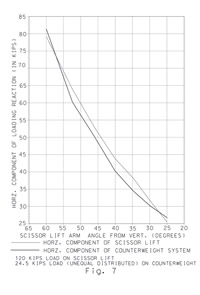

designed to vary the force applied to the

lifting arm to correspond closely with the

variation in the force required to rise and

lower the scissors lift apparatus (See Figure

7). In this way, the variable load counterweight

system is designed to effectively counterbalance

the forces in the system throughout the full

range of movement.

|

| |

The application of a variable load counterweight

system, coupled with a scissors lift apparatus,

provides a very simple means to counterbalance

the large variable forces encountered in operating

the scissors lift apparatus used to lift the

heavy retractable span. The design of the

variable load counterweight system requires

that the counterweight weigh 25 to 30 percent

of the weight of the retractable span to be

lifted. This compares to the weight of the

counterweights for a vertical lift drawbridge

— 100 percent of the weight of the span.

This is a substantial material cost savings

when considering that a typical span may weigh

250 to 1000 tons or more.

The advantages of a properly configured variable

load counterweight system coupled to the scissors

lift apparatus are

• less dead weight - In a variable load

counterweight configuration, a moment arm

is formed between the counterweight ballast

and the lifting arm creating a mechanical

advantage that magnifies the ballast load

on the said lifting arm roller allowing for

less ballast than would otherwise be required

to counterbalance the forces in the system.

• simplicity - The design is very simple

with few parts making it easy to fabricate,

install and maintain.

• reduced cost - The overall cost of

design, fabrication, materials and installation

is a fraction of that of the other methods

considered.

• reduced installation time - The time

required to install the variable load counterweight

system is also expected to be a fraction of

the time required for conventional systems.

• flexibility - The variable load counterweight

system can be configured in a multitude of

ways to effectively meet the counterbalance

needs of a specific project.

• efficiency - The variable load counterweight

system makes practical the employment of a

scissors lift (or similar) apparatus for the

lifting of very heavy loads.

Configurations

It is foreseen that there will be two configurations

of the lift-slide drawbridge — the single

leaf configuration and the double leaf configuration.

To cross the larger navigation channels, twin

opposing lift-slide drawbridges are positioned

opposite each other and the extended leaves

of the cantilevered spans are connected by a

shear lock and then lowered simultaneously onto

their piers creating a double leaf lift-slide

drawbridge as shown in Figures 8a and 8b. In

the down-closed position, the double leaf configuration

will be a three-span continuous beam with a

hinge at the midpoint of the center span and

provisions for live load uplift on the end supports.

It is anticipated that the single leaf lift-slide

drawbridge will be practical for navigation

channels up to 75' fender-to-fender clear

width. The double leaf lift-slide drawbridge

will be practical for navigation channels

from approximately 75' and greater fender-to-fender

clear width.

Conclusions

The lift-slide drawbridge is expected to

require less technical effort to design than

the conventional movable bridge types and

its fabrication is expected to require only

the standard tools and processes in a well

equipped machine and fabrication shop. It

is a low-tech solution with expected construction,

operating and maintenance costs to be equal

to or lower than the conventional movable

bridge types while using conventional components

and materials. The construction and operations

requirements for a lift-slide drawbridge should

be greatly reduced compared with those of

the conventional movable bridge types. Perhaps

more importantly, the construction time is

estimated to be approximately one year cutting

the construction time by at least half that

of the conventional movable bridge types.

The process for biding and letting a project

for a lift-slide drawbridge is expected to

be similar to that for any bridge construction

project.

With the prospective advantages of the lift-slide

drawbridge, preliminary estimates indicate

the construction cost will be approximately

50 to 70 percent that of a conventional vertical

lift drawbridge. Consider for example the

$6 million Daigleville Bridge in Houma —

the aforementioned drawbridge now under construction.

According to preliminary cost estimates, the

cost to construct a lift-slide drawbridge

at that site would be approximately $3.5 million

or a 40 percent savings.

The aforementioned $44 million Second Avenue

drawbridge in Miami, Florida — a bascule

bridge — was constructed with 2,300

tons of structural steel and 2,400 tons of

counterweight ballast steel. A lift-slide

drawbridge design constructed at the site

could reduce the structural steel by 15% and

the counterweight ballast by 70% for a total

estimated reduction in steel of 2,025 tons.

Assuming steel costs an average of $4,000

per ton, this structure would save $8 million

or 18 percent less to construct.

The cost saving in fabrication methods associated

with the lift-slide drawbridge was not considered

in these estimates. A more refined cost analysis

comparison obtained from a complete preliminary

design of a comparable lift-slide drawbridge

design and a conventional movable bridge type

at the same site will better reveal the particular

cost savings.

With continued development, there is reasonable

confidence that the lift-slide drawbridge

will become a new cost effective, functional

and versatile movable bridge type added to

the mix of the conventional movable bridge

types. It is expected to compete well and

it may become the first choice among alternatives

for most movable bridge projects.

Supplement: Variable Load

Counterweight System

To simplify the lifting components and minimize

the cost and effort required to lift the movable

span of the lift-slide drawbridge, the variable

load counterweight system (VLCS) was conceived

in conjunction with the scissors lift apparatus

(SLA) and it is in the early stages of development.

The mechanics of the VLCS are based on a relatively

simple mechanical lever principle. The findings

presented are preliminary and based on computer

analysis and 1/6 scale model testing. The

VLCS will provide:

• neutral stability counterweight function

for the SLA for the full range of its movement

• minimum power requirements as a result

of the counterweight function and

• level power requirements throughout

the operating cycle.

To design an adequate counterweight system

for the SLA three issues need to be resolved.

• The counterweight and SLA force to

lift the span are in neutral equilibrium over

the full range of the SLA movement.

• The amount of power required and its

associated cost to lift the span in approximately

30 seconds is minimized.

• The cost and time to construct the

counterweight system equal to or less than

that provided with the conventional movable

bridges; and its ongoing maintainability must

be equal to or better than that provided with

the conventional movable bridges.

To explain the mechanics behind the coupled

scissors lift apparatus and variable load

counterweight system (SLA/VLCS) it must

be envisioned how the SLA is actuated. The

horizontal and vertical force components of

the reaction from the weight of the span through

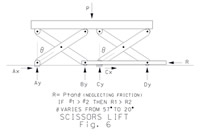

the SLA are shown in Figure

6. Following the schematic diagram shown

in Figure 6, the equilibrium of the SLA will

be maintained for its full range of movement

by opposing P; the total horizontal component

of the reactions resisting P, the weight of

the span and the SLA.

The total horizontal component of the reaction

R, is a function of the angle of the scissors

lift arm from the vertical 2, where R = P

tan(2). Given the full range of the SLA is

20E#2 #57E then for all values of

2 1 > 2 2 the corresponding

values of R1 > R2

consistently throughout the defined full range

of the SLA movement. A mechanism is needed

that will continuously apply a horizontal

force !R to oppose the horizontal component

of the reaction R over the full range of horizontal

movement of the SLA. This would place the

system in continuous neutral equilibrium over

the full range of the SLA movement.

The VLCS/SLA as shown in Figure

5 was specifically designed to produce

continuous neutral equilibrium over the full

range of the SLA movement. When the SLA is

in the down position as shown in Figure

5(a), the lifting arm roller is forced

toward the counterweight pin connection in

continuous contact with the counterweight

arm resulting in a large force directed approximately

25E from vertical producing a horizontal component

to oppose the total horizontal component of

the reaction R in the SLA resisting the weight

P of the span and the SLA. When the SLA is

in the up position as shown in Figure

5(b), the lifting arm roller is drawn

away from the counterweight pin connection

while in continuous contact with the counterweight

arm resulting in a much smaller force directed

approximately 8E from vertical producing a

horizontal component to oppose the much smaller

horizontal component R of the reaction in

the SLA resisting the weight P of the span

and the SLA.

It can be appreciated that the opposing

horizontal force produced by the VLCS will

vary continuously between the lowered and

raised position of the SLA. By design this

will produce a continuously varying horizontal

force that approximates the continuously varying

horizontal forces produced by the horizontal

component of the reaction R in the SLA throughout

its full range of movement as is the case

and shown in Figure 7.

This results in the approximate neutral equilibrium

throughout the full range of movement of the

SLA.

The SLA/VLCS is a system of connected rigid

bodies with one degree of freedom. To exchange

potential energy between the VLCS and the

SLA, there must be vertical movement of the

counterweight. This vertical movement is enabled

by the hinge support of the cantilevered counterweight

of the VLCS. To assure the potential energy

is exchanged between the SLA and the VLCS

through the lifting arm, the lifting arm roller

support relies on the SLA for stability. The

potential energy is exchanged between the

VLCS and the SLA through the horizontal force

and associated movement in the lifting arm

that couples the two.

An approximately 1/6 scale model of the

SLA/VLCS was built and initial tests using

it are consistent with the previous explanation

of the mechanics. The scale model was constructed

with a 38 lb. counterweight physically cantilevered

7.66 feet with a center of mass including

the arm located 4.00 feet from its pin connection.

A series of tests were conducted with approximately

150 lbs. simulating the weight of the span

and the SLA.

In the first test, the VLCS was uncoupled

from the SLA and the horizontal reaction R

required to lift the span and the SLA over

the full range of movement of the SLA (25E#2

#54E) was observed. The maximum horizontal

reaction R required to lift the span and the

SLA over its full range of movement was greater

than 150 lbs.

In the second test, VLCS was coupled to

the SLA suspending the 38 lb. cantilevered

counterweight on the lifting arm roller. With

no additional weight added to the cantilevered

counterweight, the maximum additional horizontal

force required to lift the SLA over its full

range of movement was reduced to 140 lbs.

In the third test an additional 37 lbs.

weight was placed on the cantilevered counterweight

arm at a position 7.66 feet from its pin connection

resulting in a center of mass located approximately

5.8 feet from the counterweight pin connection.

The maximum additional horizontal force required

to lift the SLA over its full range of movement

was 30 lbs. and the SLA/VLCS was operating

in neutral equilibrium. A summary of additional

test results is provided in Table

1.

At the neutral equilibrium achieved in the

third test, the SLA/VLCS model provided a

80% reduction in energy requirement compared

with the SLA uncoupled from the VLCS. If similar

results are obtained on a full scale, movable

bridge with a span and SLA structure weighting

300 tons the power required to lift the deck

3.5 feet in 30 seconds would be approximately

29 horsepower delivered with 4 - 6" diameter

hydraulic rams at 1200 psi.

In another series of tests, it was observed

that the force required to lift the SLA dropped

in proportion to the weight added to the cantilevered

counterweight. Weight was incrementally added

to the counterweight until the SLA/VLCS began

operating in neutral equilibrium. The maximum

force required to lift the SLA was approximately

1.5 of the calculated frictional forces in

the system. More weight was incrementally

added to the counterweight and the SLA/VLCS

continued to operate in neutral equilibrium

until the force to lift the SLA was reduced

to zero and the SLA tended to lift on its

own. These observations demonstrate that the

SLA/VLCS operates in neutral equilibrium over

a large variation in the weight of the cantilevered

counterweight.

|

| |

In conclusion, the VLCS appears to favorably

resolve the 3 previously stated issues. It

balances the forces to lift the span and the

SLA in neutral equilibrium over the full range

of movement of the SLA. It provides an energy

efficient mechanism that can readily lift

a bridge span and SLA 3 to 5 feet in 30 seconds.

The hope of minimum cost and time to construct

and good maintainability of the SLA/VLCS would

appear to be in the evident simplicity demonstrated

in the details provided.

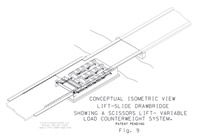

Figure 9 shows an isometric view of the SLA/VLCS

installed in a Lift Slide Drawbridge.

Table 1

|

Neutral

Equilibrium Test Data from an Approximately

1/6 Scale Model of the Coupled Scissors

Lift Apparatus and Variable Load Counterweight

System (Patent Pending)

Angle of the scissors lift apparatus

varies from 54E to 25E from vertical.

Angle of cantilever counterweight arm

varies from 16.7E to 8.4E from horizontal.

|

|

Load

on SLA (1) |

Load

on CWA (2) |

Max.

force req’d. to lift SLA (3) |

Max.

force req’d. to lower SLA (4) |

Dist.

from pin to CWA center of mass (5) |

Dist.

from pin to CWA roller (6) |

(2)/(1)

(7) |

(3)/(1)

(8) |

|

lbs. |

lbs. |

lbs. |

lbs. |

feet |

feet |

ratio |

ratio |

|

100 |

50 |

20 |

15 |

5.0 |

0.52 |

0.5 |

0.2 |

|

100 |

70 |

20 |

15 |

4.0 |

0.52 |

0.7 |

0.2 |

|

100 |

100 |

20 |

15 |

2.5 |

0.52 |

1.0 |

0.2 |

|

150 |

75 |

30 |

20 |

5.8 |

0.52 |

0.5 |

0.2 |

|

SLA - Scissors lift apparatus CWA

- Counterweight Arm

(3) Note: For all test sets, the system

is in neutral equilibrium.

(7) Note: As the distance from the pin

to the CWA center of mass increases,

the ratio of the load on the CWA to

the load on the SLA weight increases.

Note: On a working system the load on

CWA will likely be 25 to 33 percent

of the load on SLA. |

About The Author

Rex J. King, Jr., PE, is President of King &

Associates LLC, Civil, Structural and Consulting

Engineers he founded in 2000. He earned his

BS in Civil Engineering in 1993 from Louisiana

Tech University. A licensed professional engineer

in Louisiana — King has planned and designed

numerous civil and structural engineering projects

in Louisiana and he is the inventor of the lift-slide

drawbridge — patent pending — and

the variable load counterweight system —

patent pending — the subject of this article.

King is currently President of the Bayou Chapter

of the LES and a member of the ASCE, LES, NSPE,

AISC, HMS and other engineering related organizations.

|